Introduction

Pillar Point Harbor is considered an improved natural harbor. In other words, some of the harbor’s protection comes from a natural layout of the land and some from man-made improvements. In Pillar Point’s case, the improvement is the rock breakwater.

Pillar Point’s navigational suitability is quite good in a variety of seas when compared to many coastal harbors but it does have its challenges. These challenges increase as fall and winter swells arrive from the Gulf of Alaska and other far away storm centers.

We will first discuss the history of the harbor and its improvement, how reefs and shallow water effect wave dynamics and then discuss strategies to navigating to and from this harbor and some of its hazards. But first……

CAUTION!!!!

This tutorial cannot replace personal experience, seamanship, good judgement, vessel seaworthiness, safety gear aboard, etc. In no way will simply reading this tutorial solely qualify you to navigate the harbor. Each skipper must make their own decision on when and how to operate their vessel.

Also, it is vital that one review the required safety equipment and its use. If ever in doubt, or when crossing a rough entrance, have all passengers wear PFDs.

History

Pillar Point harbor has been used since the mid 1800’s as both a fishing harbor and a harbor to ship the produce from the Coastside. We must think of the area before Hwy 1 and Hwy 92 were built as an isolated, hard to reach place. Shipping was the fastest and easiest way to move products to and from the area. Pillar Point and the reefs extending from the point offered good protection from the prevailing northwest wind and swells and piers were extended out to deeper water from the shore to load and unload boats.

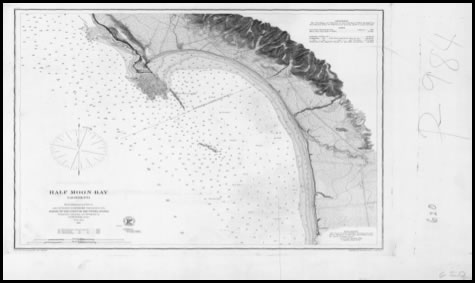

The hazards of the entrance were well known in 1863 when the below chart was made. However, no buoys existed and captains had to use whatever was available to navigate. In this chart a range marker was used between “Widow Woods” house and a spot on the hill (the line in the middle of the chart extending from shore to across the reef). Don’t ask me what they did if there was fog!!!

Although the harbor was good in summer conditions, winter storms brought high winds and big seas right into the entrance to the harbor causing great damage to both the piers and the boats moored in the bay. In fact, the crab fleet used boats that were quite small so they could be lifted from the water from the piers before an approaching storm.

In 1957 the Army Corps of Engineers built the break water as we know it today and Pillar Point became an all-weather harbor and gave us what we call “The Jaws”….the opening in the breakwater.

Wave Dynamics

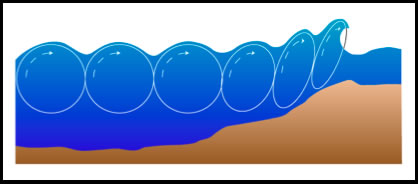

Waves are really just large circles of energy…almost perfect circles when in deep water…and you only see the tops. However, as waves come into shore and the bottom of the “circle of energy” touches the rising ocean floor the circle drags and the lower part of the circle slows down. But the energy behind tries to stay at the same speed and it has nowhere to go but up. And some point, the water can’t be held there and it falls over itself and a breaker is born.

Illustration by Pierre Granier

The Reef

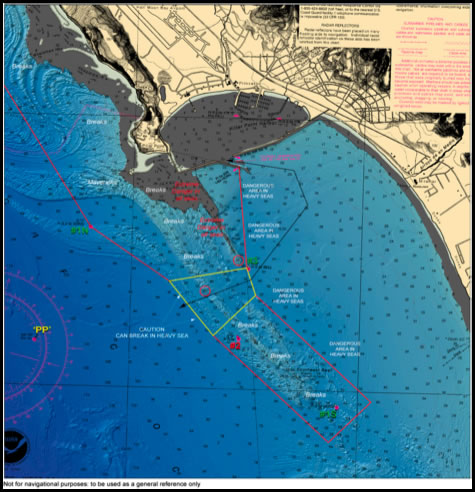

There is a large reef that extends from Pillar Point to the southeast. The reef is marked by four buoys: 1N, 1S, 2 and 3. 1N marks the northern part of the reef and must be passed to the south. 1S marks the southeast end of the reef and must be passed to the outside or the inside. 2 & 3 mark the entrance in the middle of the reef that is deep enough to pass in most conditions. Under no conditions should one try to cut across the reef except for between buoys 2 & 3. Please see the chart. The black arrow shows the recommended route by many.

Chart by Ben Sleeter

Running the Reef in a Sea

First of all, when in doubt stay in port. That being said, there are some important things to note if you should proceed.

The reef does not fully protect the inside waters from the deep water swells but rather breaks up the swell into a smaller wave but with a shorter period as they bunch up. This results in some very close, fast moving m=waves that can be very steep at times. Because of this, a straight line from the jaws to #3 is not the best course and can even be quite dangerous. Rather, allow the deeper water inside the reef to take effect and allow the wave to spread out and thus easier to navigate. So, while exiting the jaws it is often best take a route at about a 45 degree angle from the rock wall on your port and towards the beach.

About halfway there you may turn south and parallel the beach, watching carefully for any waves that you might need to “stick the pointy end into.” Once you are about 2/3 of the way abeam of the #3 buoy you can angle for a spot between #2 and #3.

Once you are through #2 and #3 you are not out of the woods. There are some pinnacles and ridges to look out for. One big one is the ridge that extends out of the reef that you would cross if you were to make a direct line between #3 and #1N. If you plan on going north past #1N it is recommended that you don’t make a straight line to #1N but rather take a course towards PP buoy until clear of the ridge and then you may proceed on your intended course. (see chart)

Another approach is to enter or exit the harbor on a course to inside #1S. The one downside of this approach is that it does leave you exposed to a beam-to sea for quite awhile. However, if you do follow this inside course there are very few shallow areas to be concerned with that can cause breakers in moderate seas. Before considering this route watch for steep swells and breakers then decide which of these two routes is safest. Remember: Its is all about safety and living to be on the water another day.

In all the above routes it is important to keep any eye out at all times for “sneaker waves” – waves that might come in larger than others. Depending on the weight, size and design of your boat you may want to be ready to turn your bow into these waves or at a 45 degree angle to them.

In a large swell depth is always your friend and keeping in more than 50 feet of water should be your goal…deeper is even better. In water over 70 feet there is little risk of a swell breaking in all but the most extreme cases. However, not that this does not mean that you cannot have dangerous wind driven waves – which is part of a different discussion.

Conclusion

Pillar Point is a fine harbor with many great benefits but, like most things in life, it has some things to beware of. However, with some local knowledge and experience the harbor can be relatively safe in most conditions. ”

It is highly recommended that you practice running the entrance in calm, clear weather several times while also using your radar before attempting it in less-than-ideal conditions. Also, be sure to know and understand how to read a chart and your GPS and how to use navigational aids. The US Coast Guard Auxiliary offers some very good and inexpensive courses that should be considered.

Every prudent mariner should have a good set of charts of their intended area and study them well. It is wise to have intended compass courses written down for the entrance not only for if the electronics fail but as confirmation that the info that you are receiving from them is accurate. Also, modern electronics allow one to know exactly where they are at a given time and what is around them…as long as the operator knows how to use them. There is no substitute for caution and knowledge.